By: Matthew Hodgson

What do smart phone apps and bricks have in common? The answer: not as much as Apple would like. While Apple v. Pepper may sound like a child’s imaginative battle between grocery items, it may prove to be the herald of cheaper products for consumers, particularly when it comes to digital software markets. In May of 2019, the Supreme Court handed down an opinion that reinterpreted the precedent of a 1970s brick-making case and opened the way for private citizens to sue Apple for overpriced software.

Many people—and even a few statistics—have noticed a common pattern in Apple’s App Store: many apps cost more money than they do on Google’s Play Store or other app-selling marketplaces. Many Apple users simply shoulder the burden or opt for only downloading free apps; but in 2011, plaintiffs led by Robert Pepper sued Apple under antitrust laws for monopolistic pricing structures. They assert that Apple holds a monopoly for app software, since its App Store is the only legally-allowed marketplace from which to buy apps. Because Apple users have no other legal options, they claim that Apple’s higher prices are symptoms of the company abusing its monopoly.

Since the lawsuit began, Apple has claimed immunity from suit. The corporation cites Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431 U.S. 720 (1977) (“Illinois Brick”), which holds that antitrust plaintiffs may only sue a company if they are a “direct purchaser.” Apple claims that these plaintiffs have purchased apps as “indirect purchasers,” since they purportedly buy the apps from app developers, not Apple.

On May 13, 2019, the Court told Apple it can no longer hide behind their pile of Illinois Bricks, and must in fact face accountability for their prices.[1] It is a complicated and nuanced case, but the bottom line is this: Pepper and his co-plaintiffs can legally sue Apple. The case moving forward from here will examine the merits of Pepper’s claim, but in the meantime—and against Apple’s wishes—the case will move forward.

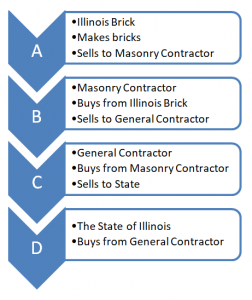

Illinois Brick, which Apple argues is an analogous case, concerned a brick market in which bricks were made, sold, sold again, and then used by the state of Illinois. The market structure looked something like this:

The State (“D” above) realized these bricks were overpriced, and so brought suit against Illinois Brick (“A”). The Supreme Court in that case held that, when a purchaser is two or more steps removed from the seller, they cannot sue under antitrust laws. In other words, if Manufacturer sells to Retailer who sells to Consumer, then Consumer cannot sue Manufacturer; only Retailer can (though, Consumer can still sue Retailer). In the graphic above, D could sue C, C could sue B, and B could sue A, but D could not sue A. The State was an indirect purchaser from Illinois Brick, and only a direct purchaser can sue.

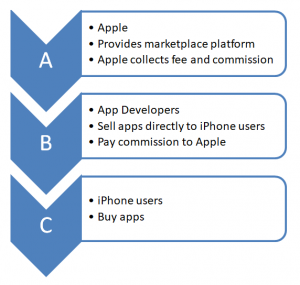

In relying on this holding, Apple claims that Pepper & Pals were not direct purchasers from Apple. Rather, Apple claims that its App Store is merely a marketplace, and the app developers set the prices and sell directly to the consumers. If Apple were to depict the market, it would look like this:

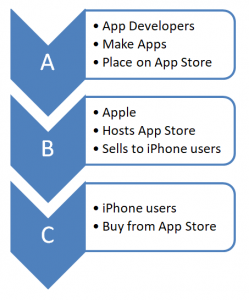

The majority does not buy this model, because app developers do not pay Apple any commission. Apple collects the money directly from iPhone users, deducts its commission, and then forwards the surplus to the developers. The Court accuses Apple of obfuscating the true picture of the market, which it argues looks more like this:

Illinois Brick, according to the Court, is not about who sets the price, but who consumers buy from. Apple charges considerably higher fees than its competitors for app developers to list apps on the App Store, but in the end, developers do set the price. The counterargument to that claim is simply that, due to the higher overhead on the App Store, developers set higher prices to recoup lost costs. The Court leaves that factual conclusion for the lower courts to decide, but allows the case to proceed on legal grounds. Whether or not Apple indirectly sets the price is for the jury to decide; whether or not Apple directly sells apps to iPhone users is a legal conclusion. Seeing as consumers’ money goes directly to Apple’s bank accounts, that conclusion seems clear.

The Court has three main reasons why it thinks Apple is economically and legally unpersuasive. The first reason is that, even though developers set the price, “retailers” usually set their price based on what the manufacturer charges. Apple says the developers are either the ones who should be sued by consumers, or the ones who should sue Apple. The Court sees this as unreasonable: on the one hand, the developers’ cost increases may be in response to Apple’s unlawful actions, so there is no fault for consumers to sue developers about; on the other hand, the developers—by raising prices to account for Apple’s unlawful actions—are ensuring that they do not suffer losses, so there are no damages for developers to sue Apple about. Apple’s “indirect” claim, under this logic, turns out to be a direct attempt to “gerrymander Apple out of this and similar lawsuits.”

Second, Apple’s suggested rule would protect some businesses and not others based on whether that business uses a markup or a commission model—a distinction the Court thinks absurd. Consider these paraphrased examples given by the Court:

Manufacturer and Retailer operate on a markup arrangement. Manufacturer sells its product to Retailer for $6. Retailer sets the price of the product by “marking it up” to $10. Consumer buys the product from Retailer. Retailer keeps the $4 profit.

Manufacturer and Retailer operate on a commission arrangement. Retailer keeps 40% of any sales as commission. Manufacturer sets the price of the product at $10. Consumer buys the product from Retailer. Retailer passes on 60% ($6) to Manufacturer.

In both examples, Consumer pays $10, Retailer gets $4, and Manufacturer gets $6. In both examples, Consumer buys from Retailer. In each example, though, a different party sets the price (Retailer in the markup, Manufacturer in the commission). If Apple’s rule (the direct seller is the one who sets the price) were adopted by the court, any antitrust violator could simply establish a commission model instead of a markup in order to avoid liability.

The Court sought to eliminate this procedural distinction by favoring substance over form. If Retailer inflates the prices, it does not matter at law what the particular business arrangement is. The third concern of the Court is this: Apple’s rule, if adopted, would provide a roadmap for retailers to avoid lawsuits simply by undertaking some fancy business organization strategies.

The final result of Apple v. Pepper is still months—even years—away. Apple may be free of antitrust liability, and its business practices may be perfectly lawful; only time will tell. In the meantime, the simple fact that the case was allowed to proceed shakes up the decades-old defenses businesses like Apple have been leveraging. The conclusion may seem simple: the person you buy from is the direct seller, but this simple distinction will protect plaintiffs and consumers against many businesses who, while not technically “setting the price,” still have disproportionate say in what that price is.

It is important to note that the holding of Illinois Brick was not overturned with this recent ruling. Its application has simply been narrowed. The business structures in Illinois Brick and Apple v. Pepper were very different, but the bottom line is the same. Maybe apps and bricks have more in common than we realize; just, not in the way Apple thought.

[1] See, Apple, Inc. v. Pepper et al., 587 U.S. __ (2019).